Italy’s public debt sustainability 2.0: the effects of a new fiscal outlook (Martin Ertl)

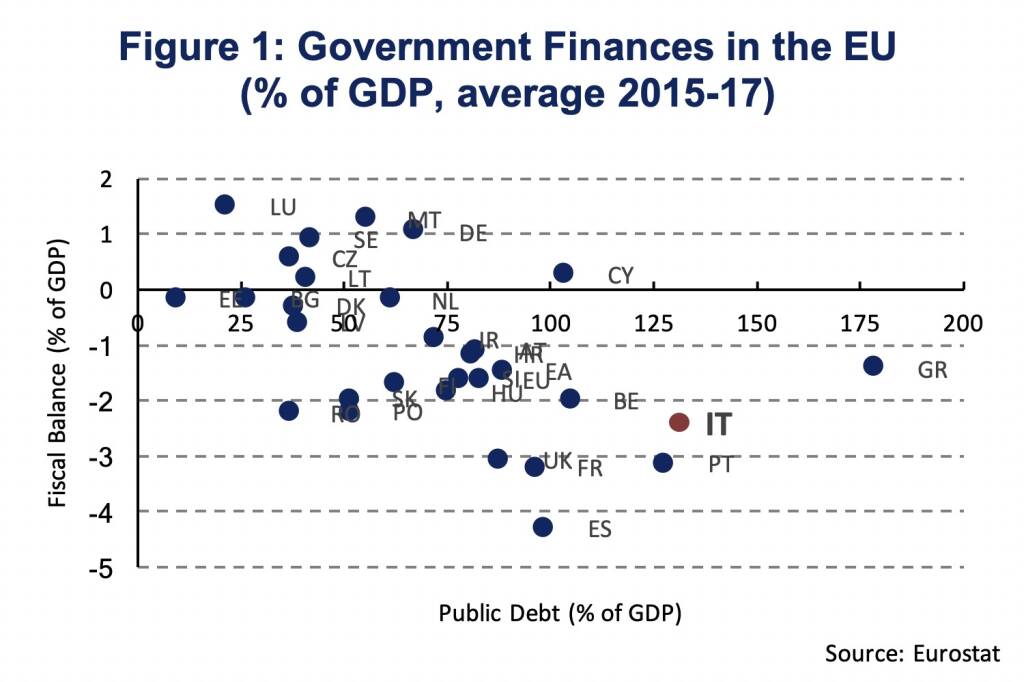

- Italy has among the highest public debt levels within the EU, only topped by Greece.

- Yet, the ruling coalition plans to raise the fiscal deficit, questioning public debt sustainability.

- The new fiscal outlook leads to a substantial deviation from the previous trajectory of public debt normalization, yet is not as excessive to make public debt unsustainable.

- Public debt to GDP will decrease only very gradually over the medium-term which does not comply with EU regulations and, if not adjusted, may results in an excessive deficit procedure.

The Italian ruling coalition, between the League and the Five Star Movement, announced its medium-term budget plan. The general government deficit was set at 2.4 % of GDP for the year 2019. This is significantly above the previous government’s deficit plan at 0.8 %, leading to headwind from the European Commission and financial markets. After 2.4 % in 2019, the deficit is planned to be 2.1 % in 2020 and 1.8 % in 2021 according to the latest announcement in early October. Italy’s budgetary plan has to be formally submitted to the European Commission by the 15th of October.

One may wonder why a projected deficit at 2.4 % is seen that critical by Italy’s European partners, given that the Maastricht criterium for the government budget deficit is 3 %. The reason is that Italy has one of the largest public debt ratios (gross general government debt in percentage of nominal GDP) within the European Union and reducing public debt ratios is a key priority. In 2017 Italian general government debt to GDP was 132 % (Eurostat). Only Greece had higher public debt ratio at 179 %. Comparing public debt and fiscal balance for all EU member states, using averages between the years 2015 and 2017, shows Italy in the right-bottom corner with a comparatively high fiscal deficit and public debt ratio (Figure 1). Hence, it should not be a surprise that fiscal discipline is a more sensitive topic in Italy than in the average EU or Euro Area member state.

With a debt burden well above 100 % of GDP, the long-term sustainability, meaning public debt to at least stay constant though preferably decrease, is of vital importance. We have performed a debt sustainability analysis for Italy already in early June (UCM Weekly) with a focus on interest rate shocks, concluding that “Italy’s debt sustains a large interest rate shock as long as the budget is kept under control”. As the fiscal outlook has changed, we update the debt sustainability analysis with a more explicit focus on the role of the deficit.

The sustainability of public debt can be analyzed quite effectively in a simple framework which is based on three key indicators: the average annual nominal interest rate paid on government debt ( , the growth rate of nominal GDP ( ) and the primary general government balance ( The debt to GDP ratio ( ) increases if average annual nominal interest rates increase, the growth rate of nominal GDP decreases or the primary balance decreases, holding all other variables constant [1].

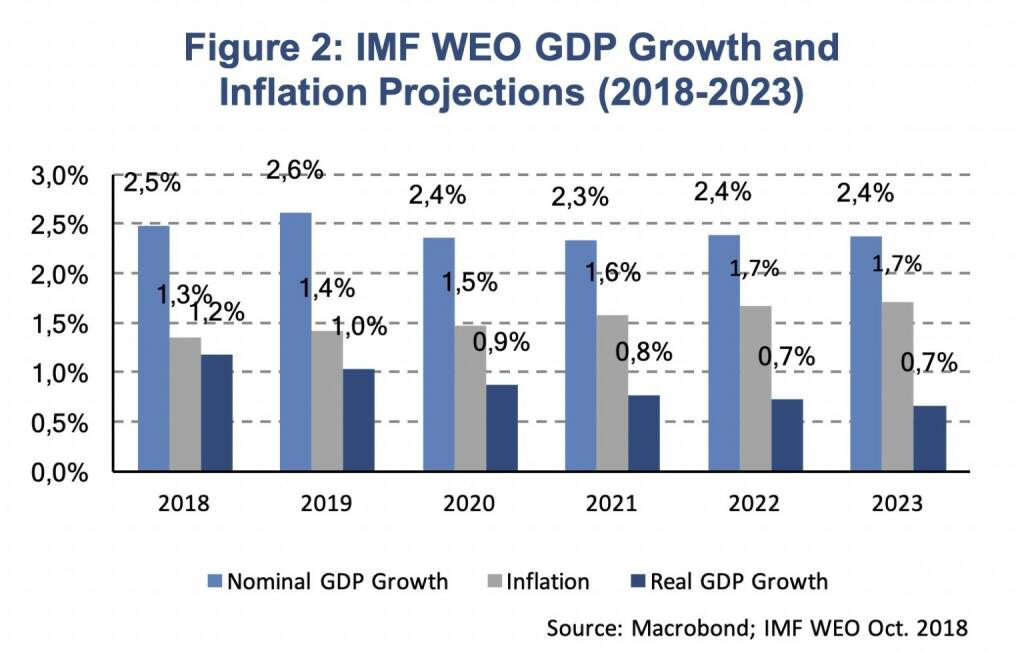

In 2017, Italy paid 62.8 bn Euro interest on its general government gross debt, which results in an implied interest rate of 2.8 %. The average residual maturity of gross debt was 7.3 years (Banca d’Italia). The weighted average fixed coupon of outstanding government securities over the next five years is 2.7 % (Bloomberg). If the Italian government wants to maintain its average debt maturity, thus issuing securities with an average maturity of about 7 years, the implied interest rate paid on government debt may remain broadly constant. The average yield of an Italian government bond with a 7-year maturity has been 2.7 % since early September. Thus, we use the implied interest rate at 2.8 % as a benchmark for Nominal GDP growth ( ) is taken from the IMF World Economic Outlook (October 2018) which projects 2.6 % for 2019 and an average of 2.4 % for the years 2020 to 2023 (Figure 2). Nominal GDP growth is mainly driven by a gradual increase of inflation to 1.7 % rather than accelerated real economic growth. GDP growth (real) decelerates to 0.7 % by 2023 which is consistent with Italy’s low growth potential at close to 0.4 % (AMECO, OECD).

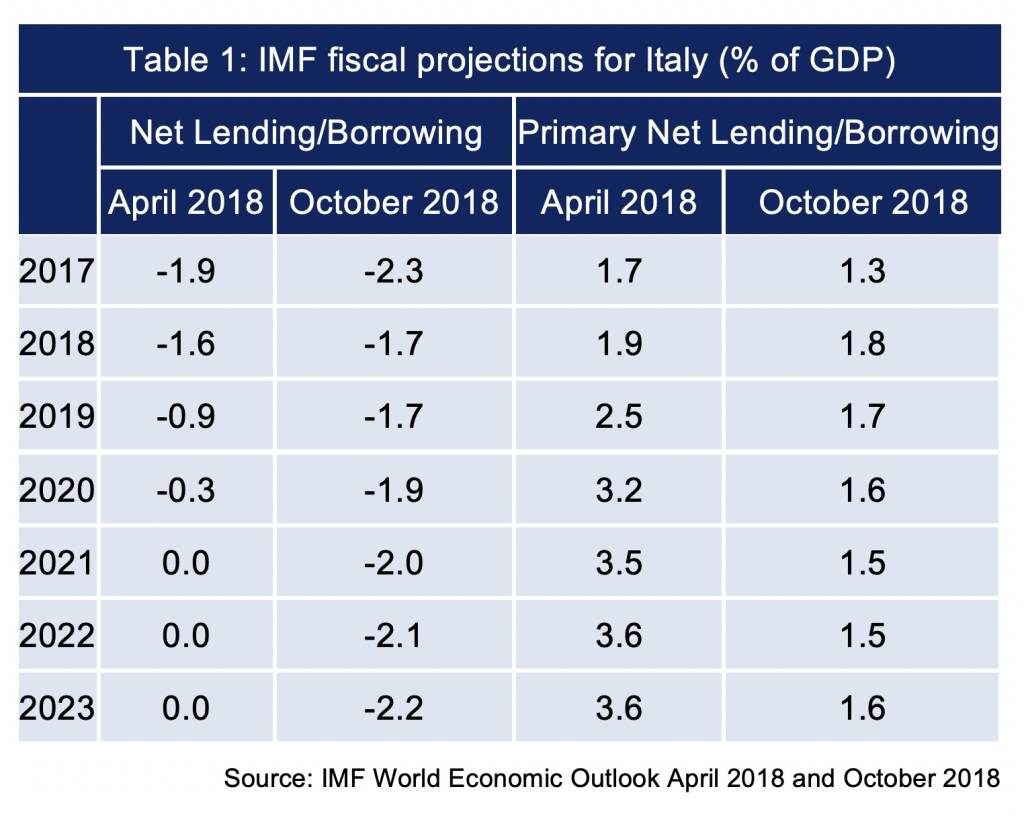

The main variable of interest in the current context is the primary fiscal balance ( , which is government net borrowing or net lending excluding interest payments on government liabilities. Compared to the IMF’s April 2018 projections, which have been used as a benchmark in our previous analysis, projections for Italy’s fiscal balance and primary fiscal balance have been lowered considerably (Table 1). While in April government finances were assumed to be balanced by 2021, the new projections show an increasing fiscal deficit to over 2 %. On average, this implies a 1.7 %-age points lower primary balance over the period 2019-23. Still, compared to the proposed budget plan, the new IMF projections show a lower fiscal deficit for the years 2019 (1.7 vs 2.4 %) to 2020 (1.9 vs 2.1 %) and a higher deficit in 2021 (2.0 vs 1.8 %).

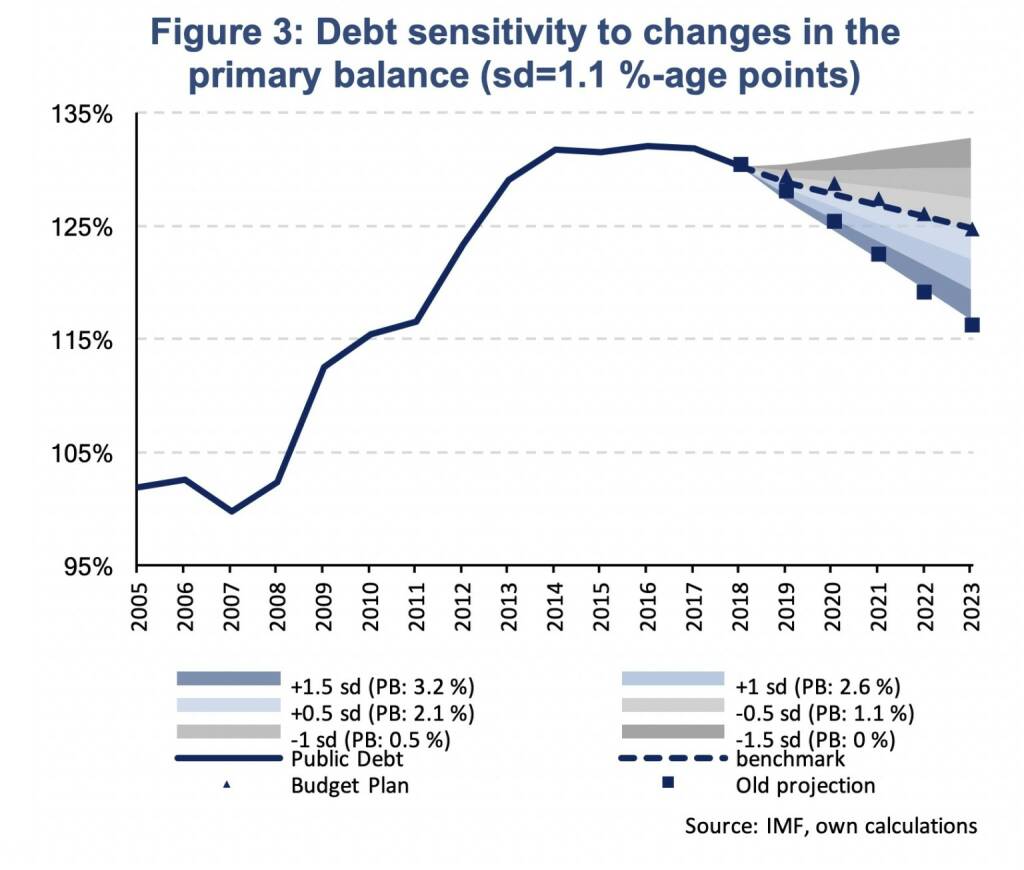

The new fiscal outlook shows a deterioration of Italy’s public debt sustainability, yet does not indicate a Greek-like scenario. As long as the fiscal deficit does not exceed 3 % of GDP, which is consistent with a primary balance of 0.5 %, Italy’s public debt will remain stable at the current level close to 130 % of GDP. In the benchmark scenario, which is based on the IMF’s latest budget projections (WEO October 2018), public debt to GDP will decline gradually to 125 % by 2023. The proposed budget plan by Italy’s new government would follow a similar pattern (Figure 3). Compared to the previous projection from June, which was based on the IMF fiscal outlook (April 2018), public debt to GDP will now be 7 %-age points higher in 2023. The rapid normalization of the public debt to GDP ratio to 2010-11 levels has become very unlikely.

In order to evaluate the sensitivity of public debt sustainability to changes in the primary surplus of 1.6 % (average of 2019-23, see table 1), figure 3 shows how the trajectory of the debt to GDP ratio would change under various fiscal scenarios. The projected primary balance is altered by multiples of its standard deviation (2000-17: 1.1 %-age points). On the one hand, a one standard deviation deterioration of the primary balance results in a stable public debt to GDP ratio. Deviations beyond that result in unsustainable trajectories. Hence, there is still some, though not a lot, flexibility to hold debt to GDP constant. On the other hand, a one standard deviation improvement of the primary balance is not enough to reach the same speed of debt normalization as in the June projection. The primary balance would need to adjust by 1.5 standard deviations in order to reach the trajectory of the previous outlook. A similar deviation in the opposite direction would make public debt unsustainable.

Thus, the new fiscal outlook shows a substantial deviation from the previous trajectory of public debt normalization, yet is not excessive enough to make public debt unsustainable. At a public debt level of 130 % of GDP, the European Commission cannot be satisfied with a budget plan which results in a reduction of 5 %-age points over a 5-year period while the previous outlook implied a reduction at almost triple that speed. Under EU regulation the debt ratio should decline by 1/20th of the gap between the actual debt to GDP ratio and the 60% threshold (Bruegel, Italy’s new fiscal plans). In Italy, this would require an annual reduction of the public debt ratio by 3.5 %-age points while our analysis shows an annual reduction by 1.1 %-age points. Thus, it is likely that the European Commission will reject the proposed budget plan. This will give the Italian government the opportunity to adjust its proposal. If the Italian government refuses to adjust its budget plan, the European Commission may open an excessive deficit procedure and after a second round of recommendations may impose sanctions.

[1] The equation can easily be derived from Auerbach, A. (1994): “The U.S. Fiscal Problem: Where We Are, How We Got There and Where We’re Going”, NBER Macroeconomics Annual 9, Stanley Fischer and Julio Rotemberg (eds.) and is a simplified version of the IMF’s DSA framework; see IMF (2013): “Staff Guidance Note for Public Debt Sustainability Analysis in Market-Access Countries”, May 6, 2013

Authors

Martin Ertl Franz Zobl

Chief Economist Economist

UNIQA Capital Markets GmbH UNIQA Capital Markets GmbH

Latest Blogs

» SportWoche Podcast #124: Liam Ferguson, de...

» Österreich-Depots: Ultimo-Bilanz mit Addik...

» Börsegeschichte 30.8.: Warren Buffett (Bör...

» PIR-News: Zahlen von Warimpex, Strabag, Ne...

» Nachlese: Karin Bauer, LLB Aktien Österrei...

» Wiener Börse Party #727: Nächster Rekord-T...

» Börsenradio Live-Blick 30/8: DAX krönt Erh...

» Börse-Inputs auf Spotify zu u.a. ATX TR, L...

» ATX-Trends: Immofinanz, UBM, CA Immo, S Im...

» Börsepeople im Podcast S14/17: Karin Bauer

Weitere Blogs von Martin Ertl

» Stabilization at a moderate pace (Martin E...

Business and sentiment indicators have stabilized at low levels, a turning point has not yet b...

» USA: The ‘Mid-cycle’ adjustment in key int...

US: The ‘Mid-cycle’ interest rate adjustment is done. The Fed concludes its adj...

» Quarterly Macroeconomic Outlook: Lower gro...

Global economic prospects further weakened as trade disputes remain unsolved. Deceleration has...

» Macroeconomic effects of unconventional mo...

New monetary stimulus package lowers the deposit facility rate to -0.5 % and restarts QE at a ...

» New ECB QE and its effects on interest rat...

The ECB is expected to introduce new unconventional monetary policy measures. First, we cal...