Quarterly Macroeconomic Outlook: Imponderability (Martin Ertl)

- Eurozone: Down to potential growth or lower

- Central and Eastern Europe: Resilient though not immune

- Financial Markets: Monetary policy normalization is coming to an end.

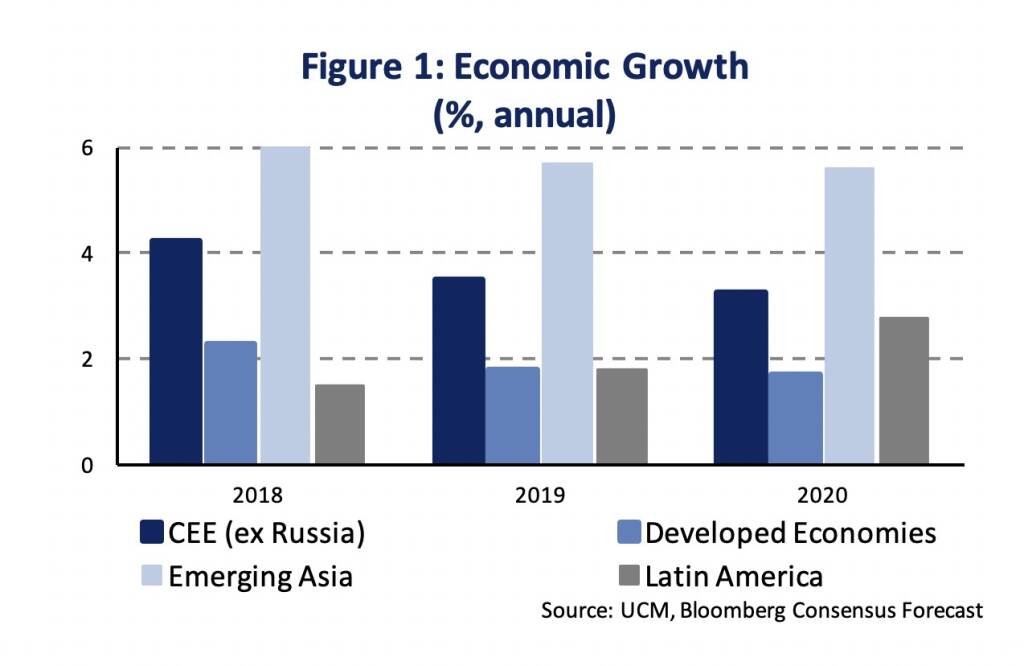

The global economy is expected to keep expanding in 2019/20 although at a slower pace than previously. Global output is forecast to grow by 3.3-3.5 % and 3.6 % in 2019 and 2020 after 3.6-3.7 % in 2018 (OECD, IMF). Hence, growth expectations neither imply a dramatic slowdown nor the onset of a global recession. Both developed and emerging economies exhibit a business cycle slowdown as well as all major regions around the globe; except for Latin America (Figure 1).

However, a lot of imponderability surrounds the current economic outlook including the evolution of the Brexit and the trade war. We do not know how and even if the UK will leave the EU during the next weeks or months. Brexit is a process, not an event. The uncertainty is affecting business sentiment and financial markets in the short-run and there is substantive literature on the long-run effects [1]. Central estimates of academic forecasts indicate a loss of 2-3 % of UK GDP compared to remaining in the EU, while subject to the type of the exit shock, estimates incorporating dynamic effects increase to a 5-8 % loss of GDP in the long-run.

After a long period of ultra-loose monetary policy and a very slow abandonment, the normalization of the interest rate environment is ending in the United States. Monetary policy of the Fed is about to reach a stance which is neither supportive nor restrictive for the real economy. On the other side, the European Central Bank’s exit from ultra-loose monetary policy has been postponed amid the growth slow down and muted inflation expectations. Basically, our main scenario for both economies is that growth is converging towards its potential growth (USA: ~2.0 %, EA: ~1.5 %).

Central and Eastern Europe has strong trade linkages with the Euro Area, most notably with Germany, and slower Euro Area growth will ultimately spill-over to many CEE countries. Thus far, the region has shunned an abrupt cooling due to healthy domestic demand. We expect to observe negative spill-over effects lagging around one year, while our CEE outlook remains solid for now.

Eurozone: Down to potential growth or lower

- The Euro Area faces a business cycle slowdown. Domestic demand remained rather resilient amid solid labor market trends. Growth is set to converge to its potential but the cyclical slowdown could get worse.

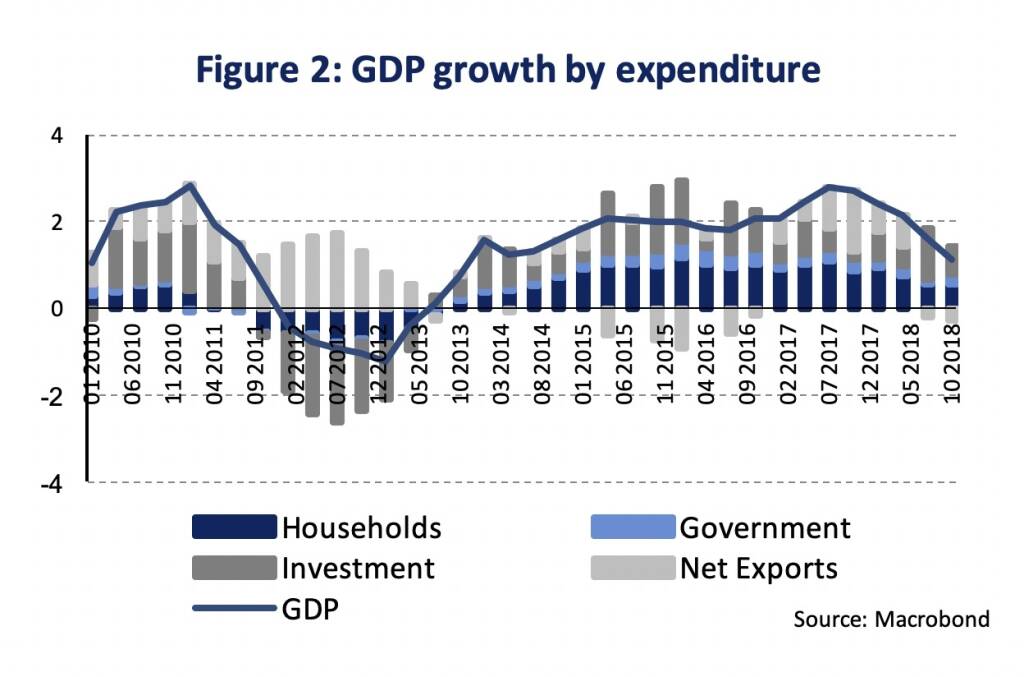

In 2018, growth in real GDP slowed to 1.7 % after 2.5 % in 2017 (Figure 2). Quarterly GDP growth average meager 0.2 % in H2 2018. The contribution of net exports to GDP growth turned negative after elevated export growth in 2017, hence, the slowdown is caused predominantly by lower external demand. In spite of a decline in business expectations, fixed investment held up well and continued to expand (0.6 % q/q and 2.8 % y/y in Q4 2018). Households kept raising consumption expenditure though at a slower pace (0.2 % q/q and 1.0 % y/y). Households’ expenditure is bolstered by a steady tightening in the labor market. The unemployment rate continued to fall (7.8 % in January). Income trends started to accelerate in 2018. Growth in labor compensation rose (2.2 % y/y after 1.6 % in 2017). Growth in total employment seems to have peaked in 2018 (1.7 % y/y in Q2), while it slowed in Q4 (1.2 %).

The Euro Area unemployment has reached a structural level (~8.0 %), however, the dispersion among Euro Area countries remains high. Labor shortages become apparent in some countries (e.g. Germany). Capacity utilization is above average, however, has not reached historical highs (Eurostat business survey). Rising investment also indicates constraints in equipment. Some indicators suggest that the Euro Area has reached its production capacity, e.g. as signaled by measures for the output gap (AMECO: +0.3 % in Q4 2018 [2]). Supply side constraints force economic growth towards a sustainable, potential growth rate (~1.5 %).

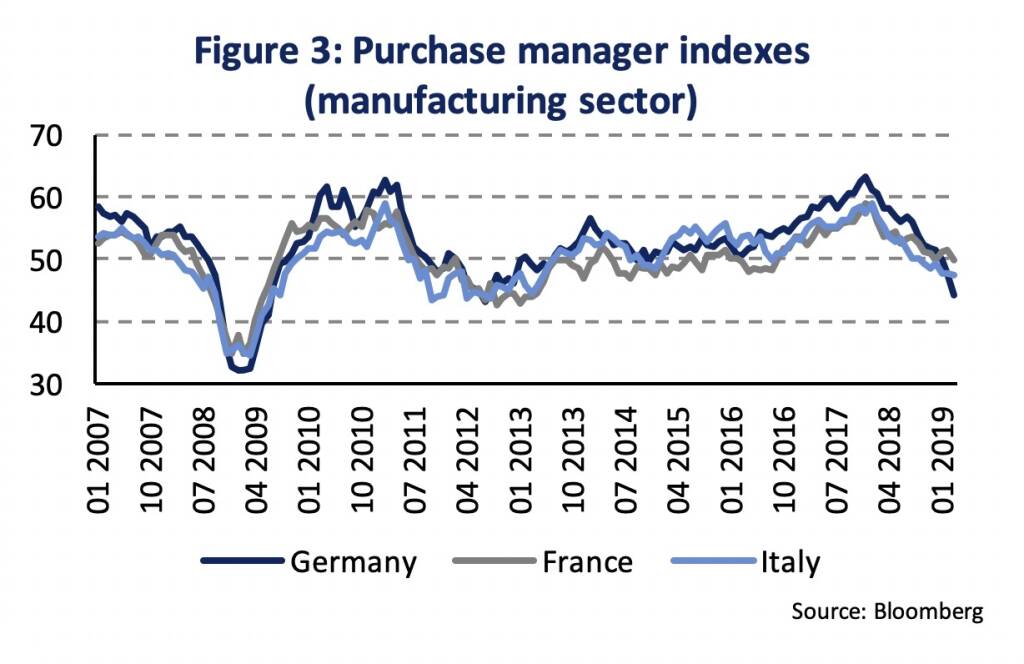

However, there is significant uncertainty about the aggregate demand. Sentiment indicators have been sliding (Figure 3). Uncertainty about Brexit and the trade war can further dampen economic sentiment and, hence, consumption and investment. Sliding export has second round effects on investment and employment. On the other side, monetary policy remains accommodative and fiscal policy turns more supportive in 2019 and cushion negative shocks.

Central and Eastern Europe [3]: Resilient though not immune

- CEE maintains solid growth. Although output expands at a gradually slower pace than in 2018, the region appears fairly resistant to the global slowdown. Inflation is mostly benign and at lot of labor markets are very tight.

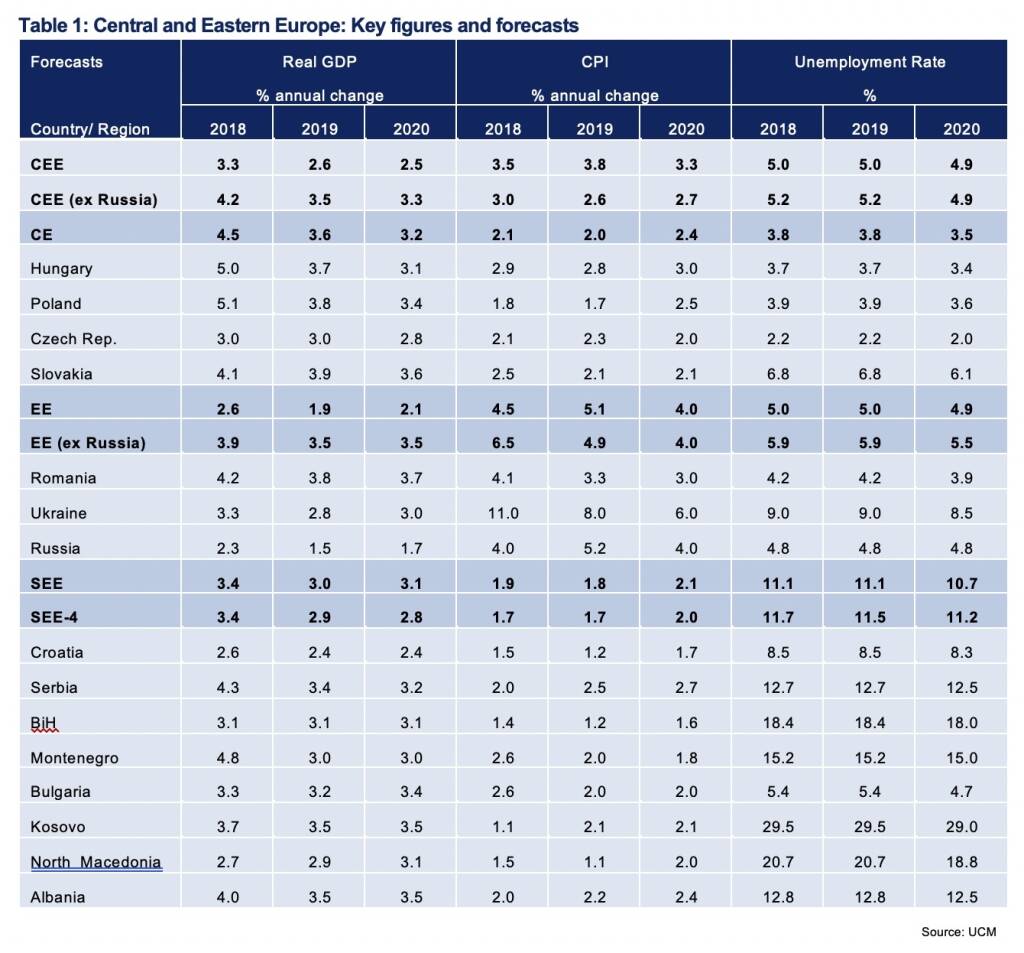

In Central Europe (CE) economic conditions remain favorable (see Table 1 for key figures and forecasts). GDP growth surprised to the upside in 2018. In 2019 growth is expected to move closer its long-run potential as capacity constraints are intensifying. Due to strong trade linkages, the continued growth slow-down in Germany remains a risk. Ultimately, slower Euro Area growth will spill-over to the region and we expect to see negative effects lagging around one year [4].

In Russia, the macroeconomic environment remains stable and the economy is expected to grow around its long-run growth potential (~ 1,5 %), yet public priority infrastructure investments increasingly seem to contribute to growth. The Ukraine economic recovery continues being driven by household consumption and investment. In Romania, economic growth has become increasingly unbalanced and dependent on household demand. With wages growing faster than productivity, structural adjustments to the economy are important in order to make growth more sustainable over the medium-term.

In South Eastern Europe (SEE) economic performance has been solid and the improvements of structurally weak labor markets is set to continue. Croatia’s economic recovery slowed down somewhat and economic growth remains heavily dependent on private consumption and tourism. Economic growth has recently been boosted by private consumption, agriculture and construction activity in Serbia. Bosnia & Herzegovina scores with a stable economic development, yet potential growth remains moderate which slows down convergence. For some years, the construction sector has been the main driver of growth in Montenegro. In case the construction boom is ending, consumption and tourism will gain importance. Substantial labor market improvements have also occurred in Bulgaria, where economic growth is close to its long-run potential. Kosovo continues a positive economic development despite a weak labor market. North Macedonia resolved the name dispute with Greece, which eases political uncertainty. The economy is back on track. In Albania economic growth has been heavily driven by the expansion in energy production.

Financial Markets: Monetary policy normalization is coming to an end.

- Changes in the growth and inflation outlook induce the European Central Bank to maintain an accommodative monetary policy for longer.

- The US Federal Reserve ends its interest rate hiking cycle based on business cycle uncertainty, signs of a cooling and stable though muted inflation.

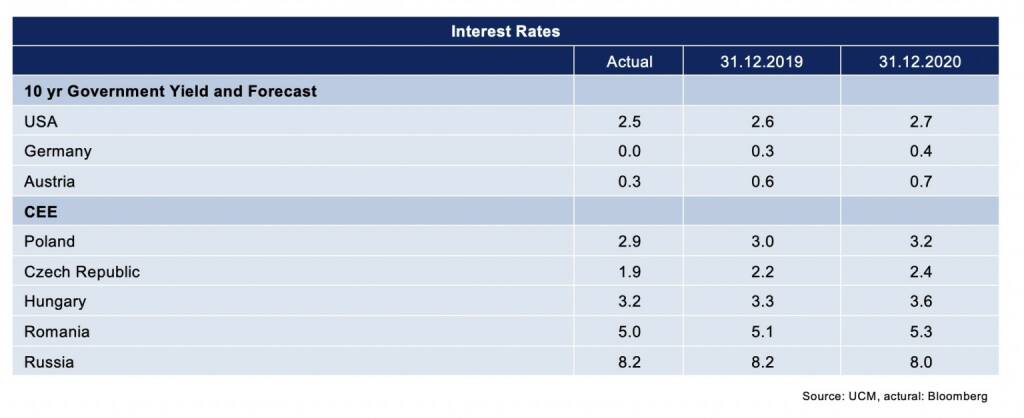

A business cycle slow-down since H2 2018 and muted inflation prospects induce a change in the ECB’s monetary policy stance. The ECB projects Eurozone inflation to remain below the inflation target at least until 2021 (2019: 1.2 %, 2020: 1.5 %). Risks for the outlook are tilted to the downside. In March, the ECB loosened monetary policy and announced additional targeted long-term refinancing operations (“TLTROs”) for banks and a change of the ‘forward guidance’. The key ECB interest rates are now anticipated to “remain at their present levels at least through the end of 2019”. Previously, the ECB had signaled that key interest rates “remain at their present levels at least through the summer of 2019”. The change in the forward guidance shifts changes in the key interest rates backward. Based on the outlook, a very slow rise in the main policy rates starting in 2020 would be an option. Nevertheless, the low interest rate environment is here to stay.

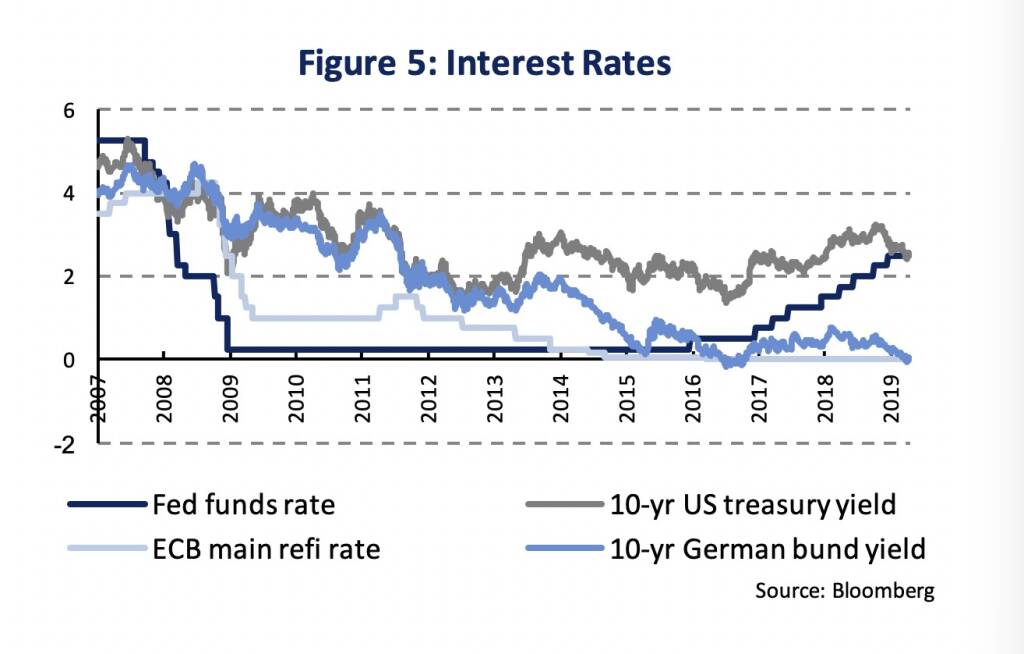

In January, the Fed changed its monetary policy stance. There are no more increases in the federal funds rate indicated after a long interest rate hiking cycle that started in December 2015 (Figure 5). The Fed gradually adjusted downward its outlook for US GDP growth (2019: 2.1 %, 2020: 1.9 %) and inflation (2019: 1.8 %, 2020: 2.0 %). The federal funds rate has reached a level which is assumed to be roughly in line with a neutral level (2.5-2.8 %). A neutral level indicates that monetary policy becomes neither supportive nor restrictive. In addition, the Fed stresses external (Brexit, trade war) as well as US business cycle uncertainty and highlights “patience” and “data-dependence” of monetary policy. The reduction of the Fed balance sheet is anticipated to end in September at a level of around 3,500 billion USD. Until December 2018, the Fed had anticipated that “some further gradual increases“ in the federal funds rate will be consistent with a sustained expansion in economic activity.

[1]For a firm overview, f. ex. see http://ftp.iza.org/dp12134.pdf

[2]The difference between actual and potential GDP. Potential GDP is a measure for full use of production sources or, in short, aggregate supply.

[3]CEE is including only countries where UNIQA Insurance Group is active.

[4]For estimates, see UCM Weekly as of 18th February 2019, http://press-uniqagroup.com/news-uniqa-capital-markets-weekly?id=79692&menueid=1684&l=deutsch

Authors

Martin Ertl Franz Xaver Zobl

Chief Economist Economist

UNIQA Capital Markets GmbH UNIQA Capital Markets GmbH

Latest Blogs

» SportWoche Podcast #155: Lili Tagger und A...

» Börse-Inputs auf Spotify zu u.a. Ex-Börseh...

» Österreich-Depots: Irre Weekend Bilanz, ab...

» Börsegeschichte 4.4.: Das wird wohl einer ...

» Nachlese: Danke Sophie Wotschke, Rudi Grei...

» Wiener Börse Party #877: Grösster ATX TR-P...

» PIR-News: Pierer Mobility, AMAG, BKS Bank,...

» 618 intraday vs. 605 (Christian Drastil)

» Börse-Inputs auf Spotify zu u.a. gettex-Po...

» Börsepeople im Podcast S18/08: Max Pohanka

Weitere Blogs von Martin Ertl

» Stabilization at a moderate pace (Martin E...

Business and sentiment indicators have stabilized at low levels, a turning point has not yet b...

» USA: The ‘Mid-cycle’ adjustment in key int...

US: The ‘Mid-cycle’ interest rate adjustment is done. The Fed concludes its adj...

» Quarterly Macroeconomic Outlook: Lower gro...

Global economic prospects further weakened as trade disputes remain unsolved. Deceleration has...

» Macroeconomic effects of unconventional mo...

New monetary stimulus package lowers the deposit facility rate to -0.5 % and restarts QE at a ...

» New ECB QE and its effects on interest rat...

The ECB is expected to introduce new unconventional monetary policy measures. First, we cal...