International trade in Central and Eastern European EU member states and non-EU accession countries (Martin Ertl)

- Trade openness is high whereby the EU is the most important trading partner.

- The structure of trade differs substantially.

- Negative EU trade balances are substantial except for the CE-4.

International trade drives economic growth. That trade should not only be seen as an important by-product of economic growth, but as a crucial determinant of higher income levels, is a widely held, well supported, though heavily debated view, in economics. Frankel and Romer (1999, p. 394), for instance, find a causal positive effect of trade on income arguing that “a rise of one percentage point in the ratio of trade to GDP increase income per person by at least one-half percent” [1]. A higher degree of trade openness is associated with more pronounced capital accumulation as well as higher productivity. For transition economies, in particular, a positive growth effect of trade liberalization has been identified [2]. The CEE region benefits from close geographical proximity to large markets of high income countries in Western Europe. Access is further facilitated by the EU membership of a growing number of CEE economies. It should, therefore, not come as a surprise that trade has been identified as an important driver of economic growth in the CEE region [3]. In this analysis we study the structure of trade among a sample of CEE economies, including EU member states and non-EU accession countries.

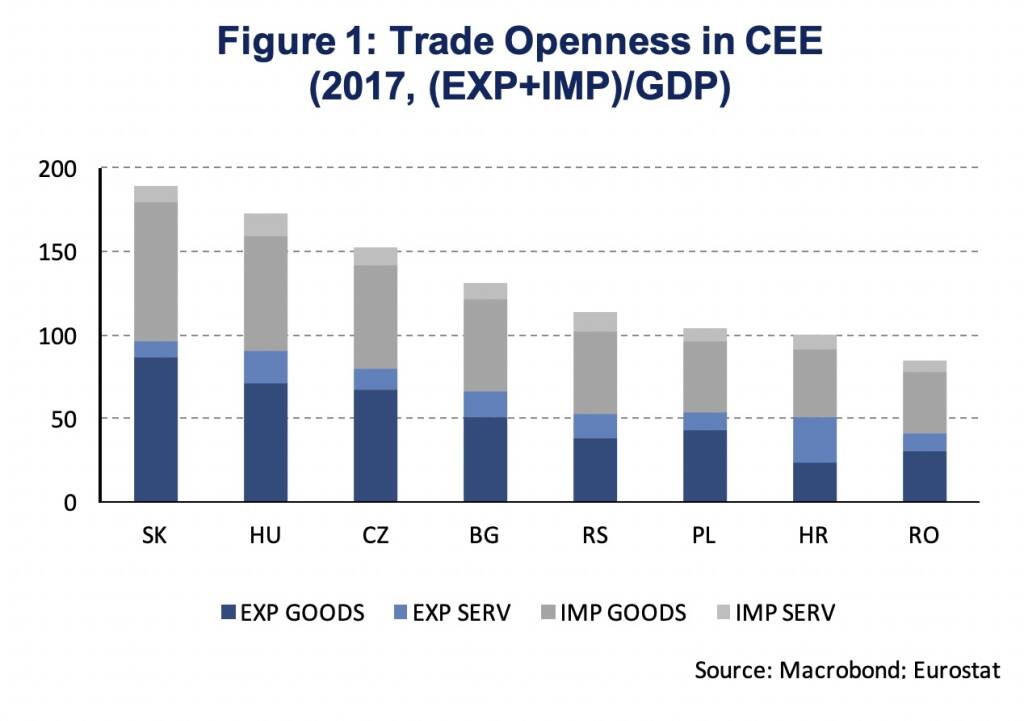

Looking at trade to GDP ratios, also known as openness ratios, shows that international trade exceeds the level of GDP in many countries of the CEE region (Figure 1). Trade in goods, rather than services, accounts for the largest share in trade openness, except for Croatia where services related to tourism are vital. The Central European economies Slovakia (189 %), Hungary (172 %) and the Czech Republic (152 %) show the highest degree of trade integration in 2017. In spite of being a EU member state, Romania shows a comparably low trade openness ratio. With respect to net exports (exports-imports), as a share of GDP, all economies except Serbia and Romania had a positive balance in 2017.

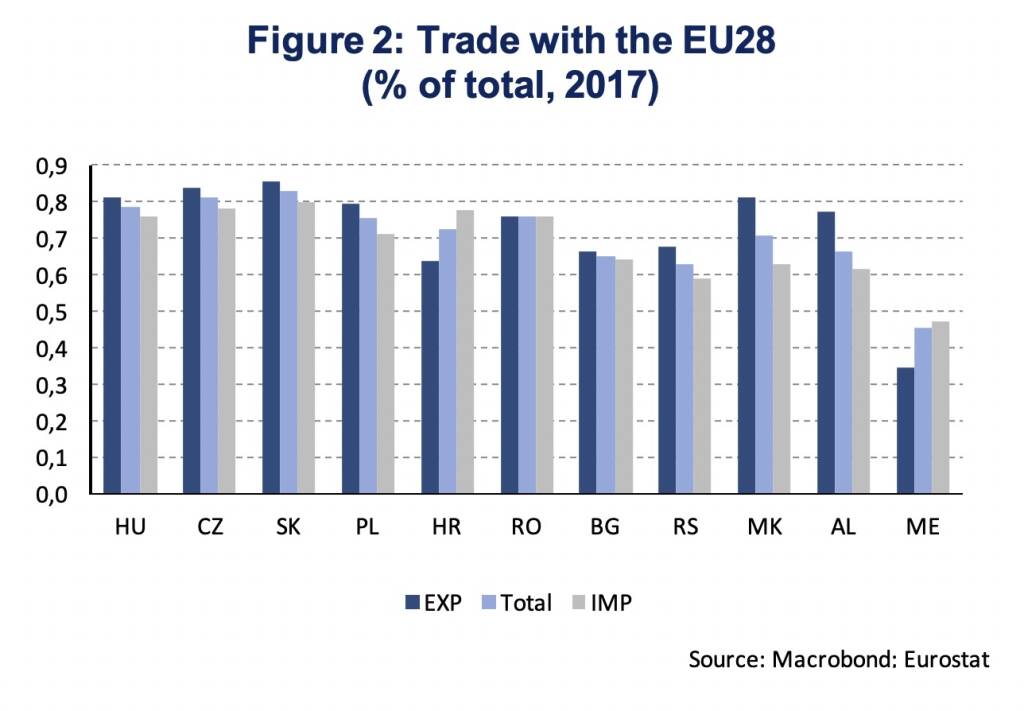

The European Union is the most important trading partner for CEE economies. Among Central European economies (CZ, HU, PL, SK) more than 80 % of exports go to other EU countries (Figure 2). EU import shares tend to be lower than export shares. Bulgaria has the lowest EU-trade share among CEE-EU countries, while Croatia is the only CEE-EU country with a significantly higher EU import, than EU export share. Besides Croatia, also Montenegro shows a higher EU import share than export share. It is important to note that the EU is by far the most important trading partner for all economies.

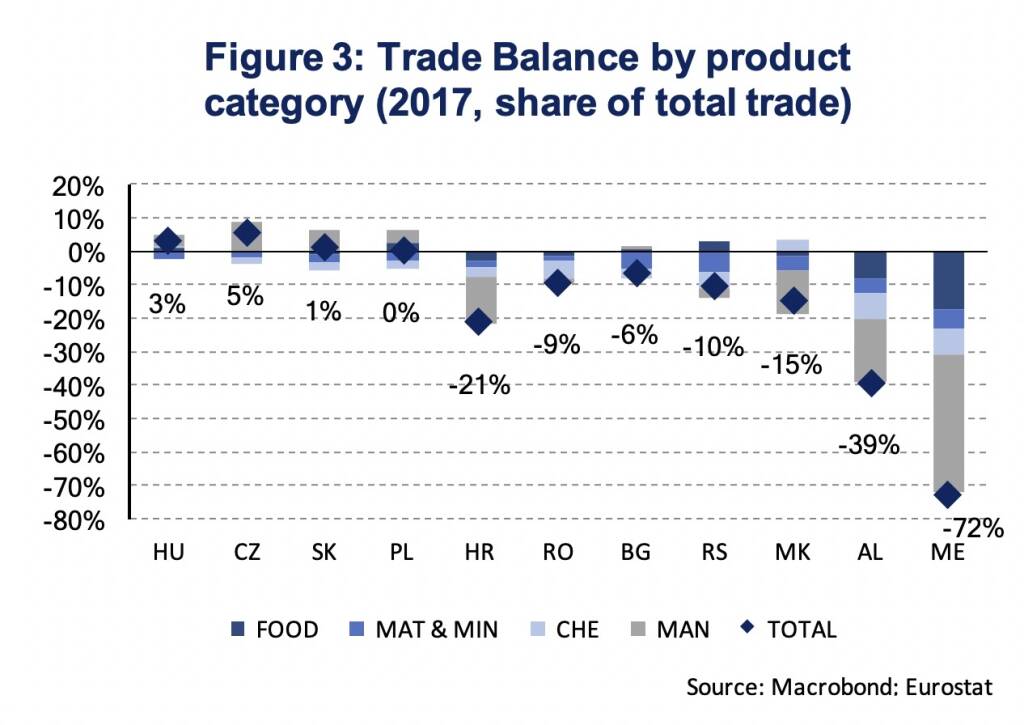

Figure 2 has shown that the relative importance of the EU with respect to international trade is remarkably similar between EU-CEE and non-EU-CEE countries. The structure of trade, however, differs substantially. Calculating the balance of trade (exports minus imports) by commodity group, being expressed as the sum of total imports and exports, gives an indication of commodity specific trade patterns. Figure 3 shows this indicator for the Food, Drinks & Tobacco category (FOOD), the Raw Materials and Mineral Fuels, Lubricants & Related Materials category (MAT & MIN), the Chemicals & Related Products category (CHE) and the Machinery & Transport Equipment and Other Manufactured Goods category (MAN). It shows that all CEE economies except for the CE4 countries have a negative trade balance (data cover goods only). This is most substantial in Montenegro (-72 %), but also Albania (-39 %), Croatia (-21 %), and Macedonia (-15 %) import significantly more than they export, as a share of total trade in goods. Disaggregated by product category shows that these trade imbalances are mainly driven by trade deficits in manufactured goods, without being compensated substantially in other categories. The Czech Republic (9 %), Slovakia (6 %), Hungary (4 %) and Poland (4 %), on the other hand, benefit from a positive trade balance in manufactured goods as a share of total trade. In Bulgaria (0 %), Romania (-1 %) and Serbia (-3 %) the trade balance in manufactured goods is either zero or slightly negative.

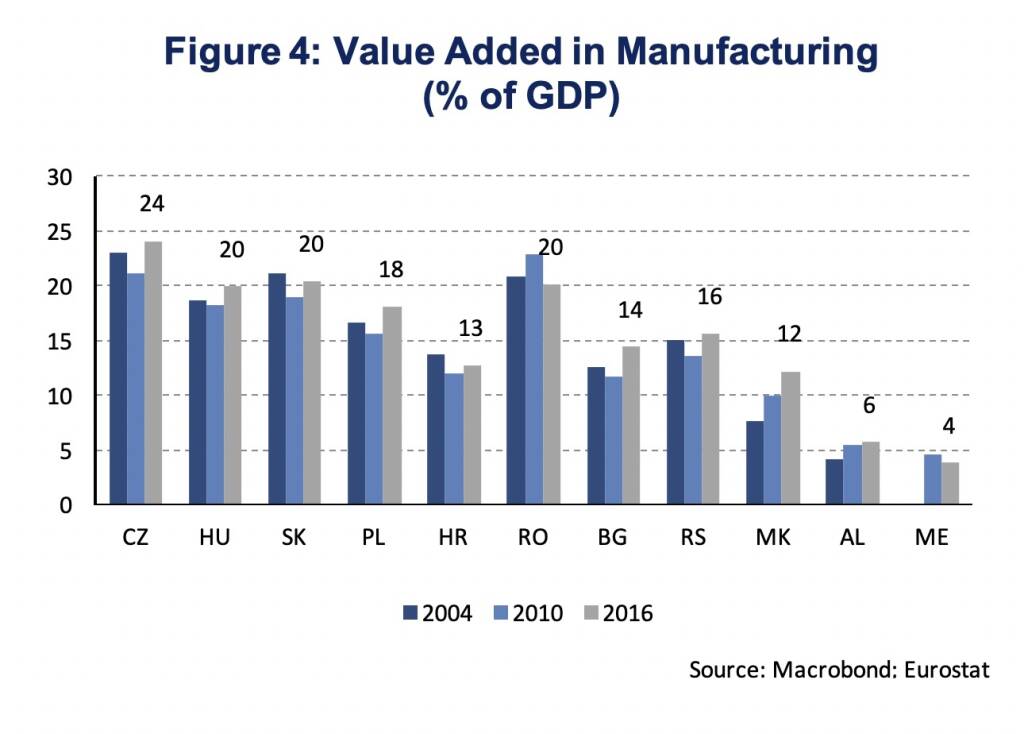

Trade in manufactured goods might be of particular importance as recent evidence highlight that global convergence was most pronounced within the manufacturing sector. Rodrik (2013, p.203) finds evidence of unconditional convergence for labor productivity within manufacturing industries concluding that “successful countries experience both productivity convergence in formal manufacturing and rapid industrialization” [4]. Among the sample of CEE economies, the manufacturing sector is strongest in the CE4 countries and Romania. Serbia, Bulgaria and Croatia show manufacturing shares above 10 %, as does Macedonia where the industrial sector has gained importance lately. In Albania and Montenegro the manufacturing sector does not play a substantial role, yet.

Overall, the analysis has shown that the trade flows of CEE economies are mainly oriented towards the European Union. Openness is high, on average, and most pronounced in Central Europe. These are also the only economies which show a positive trade balance within the manufacturing sector. Trade imbalances remain elevated in South Eastern Europe. Those countries with medium to high, or increasing, manufacturing sectors have the potential to improve their trade balance.

[1] Frankel, J. A., and Romer, D. H., (1999), Does trade cause growth? American Economic Review, 89:3, 379-399.

[2] Nannicini, T., and Billmeier, A., (2011), Economies in transition: How important is trade openness for growth? Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 73:3, 287-314.

[3] Iyke, B. N., (2017), Does Trade Openness Matter for Economic Growth in the CEE Countries? Review of Economic Perspectives17:1, 3-24.

Awokuse, T., (2007), Causality between exports, imports, and economic growth. Evidence from transition economies, Economics letters, 94:3, 389-395.

[4] Rodrik, D., (2013), Unconditional convergence in manufacturing, The Quarterly Journal of Economics,128:1, 165-204.

Authors

Martin Ertl Franz Zobl

Chief Economist Economist

UNIQA Capital Markets GmbH UNIQA Capital Markets GmbH

Latest Blogs

» BSN Spitout Wiener Börse: Wienerberger zur...

» SportWoche Party 2024 in the Making, 14. A...

» SportWoche Party 2024 in the Making, 15. A...

» Österreich-Depots unveändert (Depot Kommen...

» Börsegeschichte 18.4.: Mayr-Melnhof (Börse...

» SportWoche Party 2024 in the Making, 18. A...

» Reingehört bei A1 Telekom Austria (boersen...

» News von Verbund und VIG, Research zu Palf...

» Nachlese: Matejka Poetry Slam, B&C, 10% au...

» Wiener Börse Party #631: XXS-Folge mit ein...

Weitere Blogs von Martin Ertl

» Stabilization at a moderate pace (Martin E...

Business and sentiment indicators have stabilized at low levels, a turning point has not yet b...

» USA: The ‘Mid-cycle’ adjustment in key int...

US: The ‘Mid-cycle’ interest rate adjustment is done. The Fed concludes its adj...

» Quarterly Macroeconomic Outlook: Lower gro...

Global economic prospects further weakened as trade disputes remain unsolved. Deceleration has...

» Macroeconomic effects of unconventional mo...

New monetary stimulus package lowers the deposit facility rate to -0.5 % and restarts QE at a ...

» New ECB QE and its effects on interest rat...

The ECB is expected to introduce new unconventional monetary policy measures. First, we cal...